How the Willamette Falls Fueled Pioneers, Industry, and Innovation in Oregon City

- Robert Matsumura

- Nov 17, 2025

- 4 min read

Nestled at the base of Willamette Falls, just 13 miles south of Portland, lies a city that was once viewed as a symbol of hope, grit, and new beginnings. Oregon City — modest in size today — was once the ultimate destination for tens of thousands of immigrants who braved the 2,000-mile journey along the Oregon Trail. It was the end of the line, and the beginning of a new life.

The Trail Ends Here

By the 1840s, word had spread across the American Midwest and beyond: a bounty of fertile land lay in the Oregon Country. The Oregon Trail itself was a ribbon of ruts stretching from Independence, Missouri to the verdant valleys of the Pacific Northwest. This was no neatly laid path, but a brutal and often heartbreaking test of endurance. Families traveled by wagon train through plains, over mountain passes and across rivers, risking disease, starvation and mishaps.

But why Oregon City?

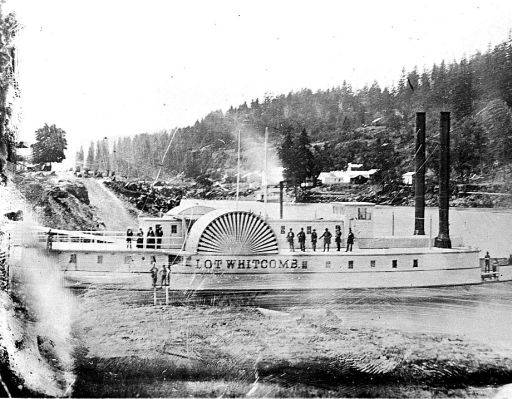

A mix of geographic, economic, and political factors coalesced in this place. Located just below Willamette Falls, Oregon City resided at a natural terminus — one that made sense not only logistically, but symbolically. The Willamette River was navigable only as far as the falls, which meant settlers arriving via the Columbia could continue south by boat until reaching this dramatic natural phenomenon. Settlers then used native portage trails on each side of the river to transport wagons, livestock, gear, and boats to the city below. In 1873 the Willamette Locks were built allowing boats to bypass the falls.

Oregon City also lay at the edge of the fertile Willamette Valley — the promised land so many immigrants sought. As the first significant settlement in the region, it offered the first opportunity for pioneers to register land claims, purchase tools, and begin life as homesteaders under the newly formed Provisional Government. It was, in effect, the portal to the future.

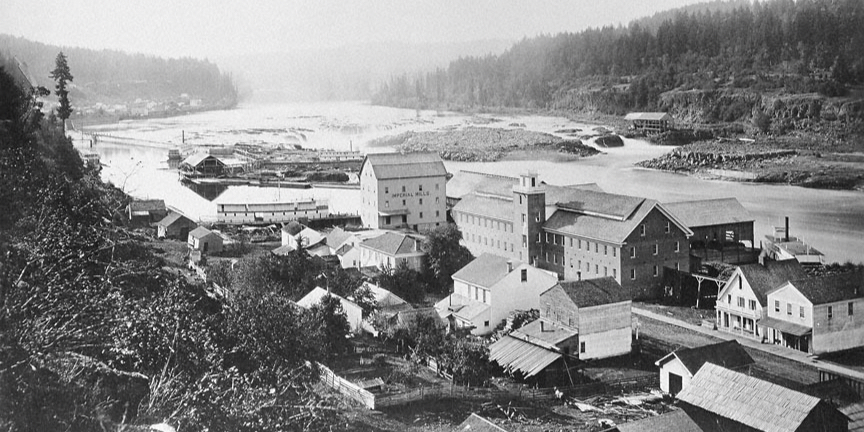

When the first major wagon trains arrived in Oregon City, the town was already taking shape. In 1829 Dr. John McLoughlin, the influential Hudson’s Bay Company official stationed at Fort Vancouver, selected the site for a lumber mill. Though a British subject, McLoughlin welcomed and aided American settlers — often at odds with the Company’s interests. He provided supplies, medical aid, and advice, and his support helped cement Oregon City's role as a refuge and staging ground for weary travelers.

By the time the U.S. formally organized the Oregon Territory in 1848, Oregon City was a well-established center of commerce and administration. For the thousands who had risked everything to reach the West, this modest town on the river was the realization of a dream.

A City of Firsts

Officially chartered in 1844, Oregon City was the first incorporated city west of the Rocky Mountains. It was home to the first Protestant church west of the Rockies, the first newspaper (The Oregon Spectator), and the first territorial capital of Oregon. But more than these distinctions, Oregon City was a living junction of cultures, aspirations, and histories.

The new settlers poured into Oregon City with hope and optimism, but others were experiencing the opposite. The new city sat on ancestral lands of the Clowewalla — a Chinookan people who had dwelt along the Willamette River for centuries, fishing the falls for salmon and trading with other indigenous peoples throughout the region. The arrival of settlers dramatically disrupted their way of life, representing the human cost tied to America’s Westward expansion.

The Power of the Falls

The Willamette Falls — second only to Niagara in volume — was more than a picturesque backdrop. It was the city’s industrial engine. With the falls came the potential for hydropower, and in the 19th century that potential was fully realized.

Oregon City became one of the earliest cities in the world to harness hydroelectric power. In 1889, electricity generated at Willamette Falls was transmitted 14 miles to Portland — marking the first long-distance transmission of electricity in the U.S. For a brief moment, Oregon City represented the vanguard of technological innovation.

Mills and paper factories sprang up along the riverfront. Logs floated down the river from the forests and were turned into paper, powering an economic boom. Oregon City grew — modestly compared to settlements — but retained its identity as a place built on grit and river power.

A Living History

Today, Oregon City embraces its past with open arms. The End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center is a must-visit for locals and travelers alike. It’s not just a museum — it’s an immersive experience. Inside its iconic, covered-wagon-shaped buildings, you’ll find exhibits on pioneer life, hands-on activities for children, and living history demonstrations. For families descended from Oregon Trail pioneers, the interpretive center provides genealogical research services as well — a personal touchstone to the past.

Nearby is Dr. John McLoughlin’s house, perched on the bluff above the river. The home of the “Father of Oregon” is now restored as a National Historic Site offering a personal window into the lives of those who shaped the region.

The Modern City

A town with deep historic roots, Oregon City is undergoing revitalization. Boutiques, breweries, cafés, and galleries are bringing new life to old buildings. The city has also reconnected with its waterfront, launching redevelopment efforts to reclaim the former industrial mill land near the falls.

Perhaps one of the most unique features of modern Oregon City is its municipal elevator. Built in 1915 and updated in 1955, it remains one of only a handful of vertical street elevators in the world. It connects the lower riverfront district to the upper bluff neighborhood—and it’s free to ride.

The Legacy

Oregon City doesn’t shout for attention: it whispers to those who know how to listen. It’s in the echo of wagon wheels and the roar of Willamette Falls. It’s in the quiet dignity of settlers, and the voices of Native peoples whose lives were irrevocably altered.

To walk through Oregon City is to touch the end of one story and the beginning of another. For the pioneers, it was the end of the Oregon Trail. But for us, it's an invitation to understand where we come from, and, perhaps, where we’re going.

Because the Trail never really ends. It just changes direction.

Comments